Josephine Butler: a very brief history

Last year a biography of one of the prominent social reformers and fighters for women's rights, Josephine Elizabeth Butler (1828-1906), was published. Although there have been several books written about her life -including an autobiography- this new publication by Jane Robinson contains only 91 pages. (1) And even more striking: Josephine's life story from birth to death in chronicle order is told from pages 5-39. A remarkable book about a remarkable person.

Collecting stories

Having a political reformer and abolitionist father combined with a Huguenot Christian mother, clearly influenced Josephine on her journey. At a young age, she marries George Butler, a schoolteacher and academic who would unconditionally support his wife's choices. The couple has four children of which their eldest daughter has a fatal accident in 1864. It is after this tragedy that Josephine starts becoming more actively involved in charity work and the abolitionist movement.

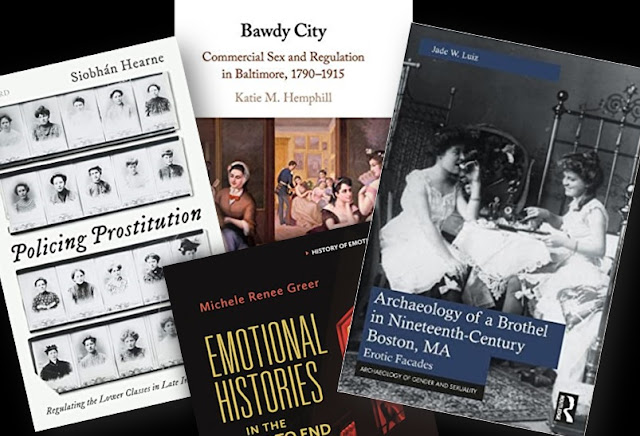

"Women of the city"

Josephine regards prostitutes or "women of the city" as she called them, to be sinners. However, they are not the only ones. Men who bought sex are "at least as culpable as the women who sold it" (p. 17). But the social reformer is also convinced that sinfulness can be cured, through redemption, faith and education. (p.18) The home of Josephine and George in Liverpool, therefore, becomes a refugee for former 'fallen women'. Josephine's ambitions reach beyond offering local aid. By initiating a successful national campaign she manages to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts. (2) Her determination also leads in 1886 to raise the age of consent for women in the United Kingdom from 13 to 16 years. To achieve her goals Josephine travels for support across the country, as well as abroad. She also organizes lectures, writes books and publishes pamphlets.

Collecting stories

To draw publicity for her cause, collecting and spreading the stories of victims are essential. An interesting question, that is not raised in the book, is to what extent this information was perhaps altered to serve abolitionist goals? Josephine talked for instance about a British young woman from Nottingham, Mary MacLaughlin, who was supposedly misled when she looked for an "honest situation" in Brussels. (3) Yet, conflicting to her report, the woman in question, Mary, declares that she consciously chose to work in a brothel and since she still earned her living as a prostitute in Belgium two years afterwards, her statement seems genuine. (4) Mary was part of the first white slavery court cases in Brussels. Although the cases are mentioned, the author does not raise critical questions on the topic. Yet, it could have given a more indebt insight. A sharper approach is also missing in the second part of the book on Josephine's legacy. She is described by a co-worker at the time as an "almost ideal woman" (p.43) and the author agrees and declares that even the recent #metoo movement is nothing new. Josephine thought of it before we did. (p.62)

Concluding remarks

On the positive side, in general, l really enjoyed the clear style of writing of the author and the short biography part on Josephine's life. Josephine was a prominent social reformer determined to improve women's rights and their access to education. This book honours that. It would have been more convincing, though, if it included critical insights into how these goals were reached. Proving that Josephine accomplished remarkable things on the one hand, but was, on the other hand, not a saint either.

Notes

(1) J. Robinson, Josephine Butler: A very brief history (London 2020). I have read the e-book version.

Also recently republished is for instance: Helen Mathers, Josephine Butler. Patron Saint of Prostitutes (2nd rev. ed; Cheltenham 2021).

(2) See also more information on this topic and interesting archive of the associated Ladies National Association can be found on: https://archiveshub.jisc.ac.uk/search/archives/c1797273-1af3-349d-b16e-0ce3dacdce94 [visited on: 14-11-2021]

(3) J. Jordan and I. Sharp (eds), Josephine Butler and the Prostitution Campaigns. Diseases of the Body Politic Volume IV (London 2003) 66.

(4) Information from the court record archive of the White Slavery case of 1880 and the city archives of Brussels and Antwerp. I told the story of Mary at the Secret Lives Conference (see slides 27 and 28).

Related blog posts

Comments

Post a Comment